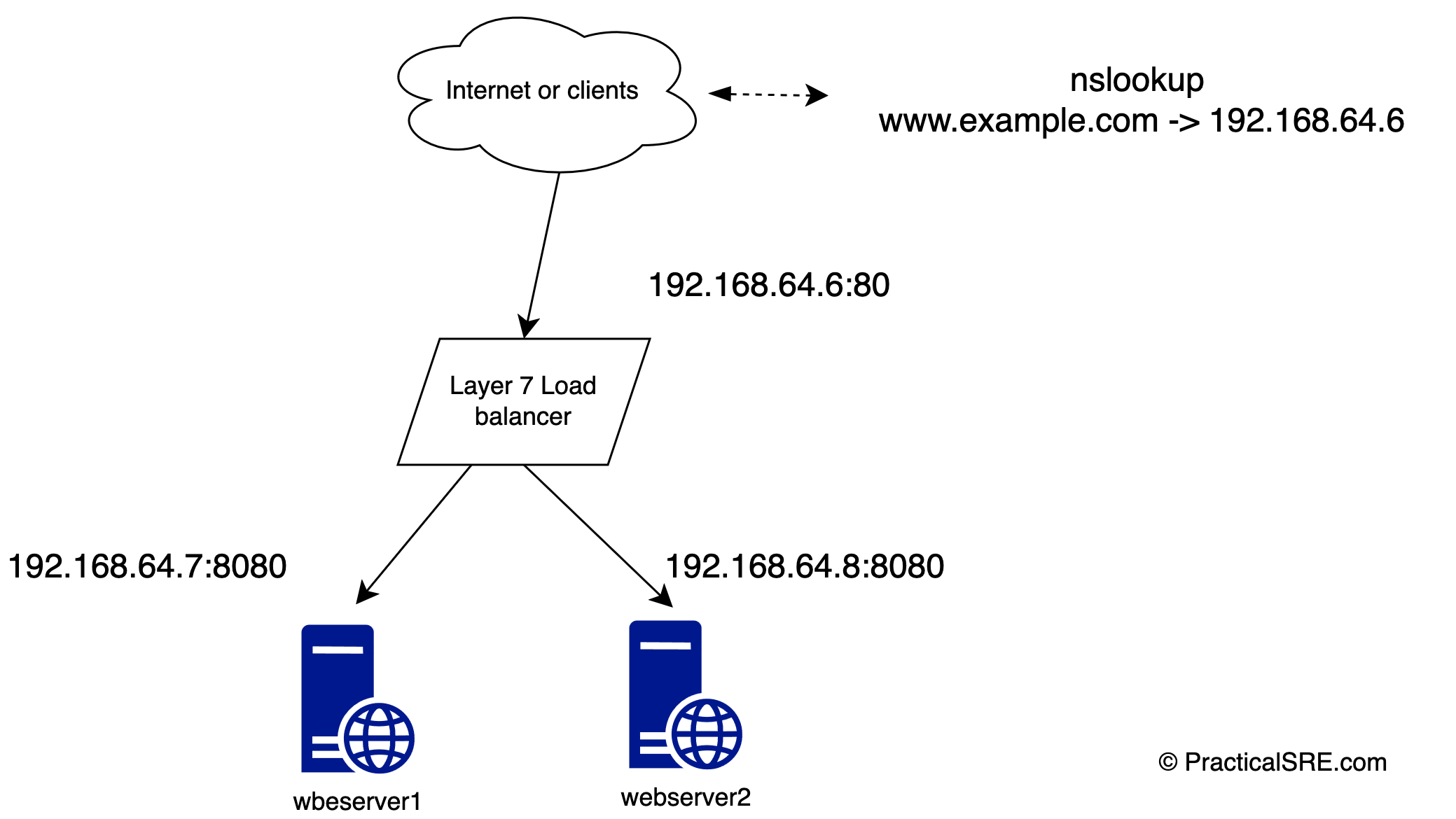

In a very basic web architecture, a load balancer is used to distribute traffic evenly between two or more downstream application/web servers to provide redundancy in case one webserver goes down. Here is a diagram that illustrates this. It shows a layer 7 load balancer (HAproxy) that accepts traffic on port 80, and forwards it to the backend webserver1 and webserver2 in round robin fashion. If webserver1 goes down, haproxy can seamlessly forward all packets to webserver2 instead.

But what happens when the load balancer itself goes down? This is a crucial but all too common problem when designing or building a high availability system.

The obvious solution is to add a second load balancer to act as a backup in case the primary fails. Nowadays software load balancers are all the rage due to low cost and flexibility. Hardware load balancers are expensive and not easily scalable.

This sounds logically simple, but the technical challenge here is what or who will load balance the load balancers? Since each load balancer has its own IP address, what happens when one load balancer goes down? How would we shift traffic over to the backup load balancer host? DNS can do this by handing out two A records, but not without several drawbacks, such as long TTLs, or clients caching IP addresses and not honoring TTLs at all. DNS is not the preferred solution here, it will cause an outage, perhaps a brief one if we are lucky.

VRRP to the rescue

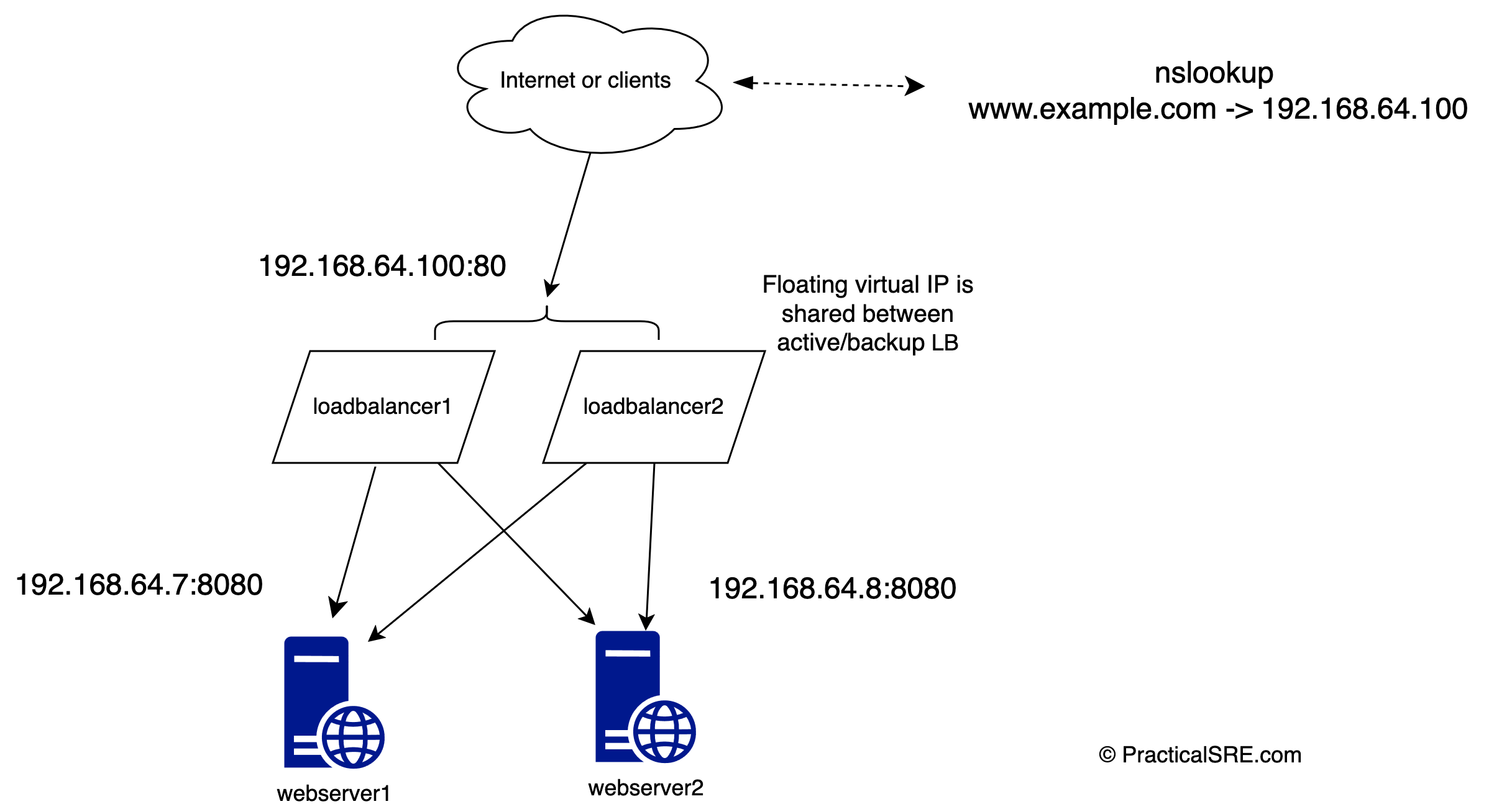

I present to you the concept of a floating Virtual IP or VIP; One VIP is shared among two load balancers dynamically, on the fly. The VIP will be assigned to one primary node, and when that node goes down, the Virtual IP should switch over to the backup node automatically! This is effectively a Layer 3 high availability failover solution and should not be misconstrued as load balancing. The load balancing part is done by the haproxy instances.

From the client or user’s perspective, nothing changes, they will not even notice any outage as the IP address failover happens in real time. Clients continue to connect to the same virtual floating IP address. This is done by a software called Keepalived, and it uses a network protocol called VRRP. Virtual Router Redundancy Protocol. The beauty of this setup is that VRRP works at Layer 3 (network layer), meaning it can be used for any service regardless of protocol or port numbers.

Let’s demonstrate this in practice by setting up the design in the diagram using an Ubuntu virtual machine lab.

In this article, we will create 4 ubuntu virtual machines, two will be the load balancers, and two will be the web servers. Our goal is to configure these so that the system remains highly available and fault tolerant even if one load balancer goes down or one web server goes down.

Use a virtual machine hypervisor of your choice such as VirtualBox to create 4 Ubuntu LTS machines like shown in the table. Minimum specs are enough for this, 1GB ram, 1 Core. The IP address can be defaults, you just need to make note of them. Make sure the machines are able to talk to each other. In this lab, I used multipass, a handy tool from Canonical to create the VMs. It makes creating Ubuntu VMs incredibly easy.

brew install multipass #install multipass on a macbook

multipass launch lts --name loadbalancer1 #this creates an ubuntu lts virtual machine

multipass launch lts --name loadbalancer2

multipass launch lts --name webserver1

multipass launch lts --name webserver2

multpass shell loadbalancer1 #login to the host

This table shows the configurations on my lab environment.

| Hostname | IP | Components |

|---|---|---|

| loadbalancer1 | 192.168.64.5 | Install haproxy and keeaplived |

| loadbalancer2 | 192.168.64.6 | Install haproxy and keeaplived |

| webserver1 | 192.168.64.7 | Deploy a web application on port 8080 |

| webserver2 | 192.168.64.8 | Deploy a web application on port 8080 |

Layer 7 load balancer setup with Haproxy

Run this command in both load balancer designate nodes loadbalancer1 and loadbalancer2 to install haproxy. We will be using haproxy as a layer 7 load balancer.

$sudo apt install haproxy -y

Replace the haproxy config /etc/haproxy/haproxy.cfg with this:

defaults

mode http

frontend www

# receives traffic from clients

bind :80

default_backend web_servers

backend web_servers

# relays the client messages to backend web servers round-robin by default

server webserver1 192.168.64.8:8080 check

server webserver2 192.168.64.7:8080 check

Restart haproxy on both loadbalancer1 and loadbalancer2 so that the config takes effect.

$sudo systemctl restart haproxy

Deploy the sample webservers

You can run any sample flask app here, or deploy a pre-built docker container. Anything will do as we only want to serve a barebones http server to connect to to show the load balancer works. Here’s what I ran in this instance.

webserver1 and webserver2 are listening on port 8080 and serving up a python flask web application. The application simply displays the hostname and IP address used to make any outbound connections (get_ip_address function is used since we don’t want it to print loopback IP)

from flask import Flask,render_template

import socket

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route("/")

def index():

try:

host_name = socket.gethostname()

host_ip = get_ip_address()

return render_template('index.html', hostname=host_name, ip=host_ip)

except:

return render_template('error.html')

def get_ip_address():

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_DGRAM)

s.connect(("8.8.8.8", 80))

return s.getsockname()[0]

if __name__ == "__main__":

app.run(host='0.0.0.0', port=8080)

Run the python webapp on both web servers

webserver1$ python app.py

* Serving Flask app 'app'

* Running on all addresses (0.0.0.0)

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:8080

* Running on http://192.168.64.7:8080

webserver2$ python app.py

* Serving Flask app 'app'

* Running on all addresses (0.0.0.0)

* Running on http://127.0.0.1:8080

* Running on http://192.168.64.8:8080

Layer 3 Failover setup by with Keepalived

Now that both our Layer 7 haproxy load balancers effectively load balances between the two backend webservers, we need to configure failover between the loadbalancers themselves. For this failover setup of the floating Virtual IP (VIP) we will use a popular and robust software package called keepalived.

Run this command in both load balancer designate nodes loadbalancer1 and loadbalancer2 as a prerequisite to installing keepalived.

$sudo vim /etc/sysctl.conf

#Add the following line:

net.ipv4.ip_nonlocal_bind=1

#Restart sysctl:

$sudo sysctl -p

This allows the ubuntu machine to accept connections over a virtual IP.

Next, install keepalived on both load balancer nodes and create a config file.

Edit the keepalived config on each host with this.

$sudo apt-get install keepalived -y #install keepalived

$cat /etc/keepalived/keepalived.conf

! Configuration File for keepalived

vrrp_instance VI_1 {

state MASTER

interface enp0s1

virtual_router_id 51

priority 101 #This should be set to lower priority like 100 on the backup machine

advert_int 1

authentication {

auth_type PASS

auth_pass 1111

}

virtual_ipaddress {

192.168.64.100

}

}

$sudo systemctl restart keepalived #restart keepalived on both hosts

The only difference between loadbalancer1 and loadbalancer2 config is the priority, loadbalancer1 has 101 and loadbalancer2 has 100. Since 101 has higher priority, it is designated as the primary, and will handle normal day to day traffic. When the primary goes down or is unreachable due to hardware, or network failure, the backup automatically takes over.

virtual_ipaddress - 192.168.64.100 is the key config here. This is a made up IP address that hasn’t been assigned to any machine in the local network. If using this on a public/internet facing network, you would use a static public IP address purchased from a provider.

Let’s look at the keepalived logs:

As we can see, lb1 and lb2 communicate between themselves and elect the leader, that is the host that has higher priority.

Now let’s shut down loadbalancer1, You can shut keepalived or even the linux vm itself. “sudo systemctl stop keepalived” or “sudo shutdown now”

Refreshing the client’s browser continuously, we can see that the VIP continues to return 200. No outage experienced!

Additionally. ping from a client terminal shows that there was a single instance of packet drop when the VIP switched from primary to backup.

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=108 ttl=64 time=1.769 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=109 ttl=64 time=4.241 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=110 ttl=64 time=1.528 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=111 ttl=64 time=1.753 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=112 ttl=64 time=1.691 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=113 ttl=64 time=2.250 ms

Request timeout for icmp_seq 114

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=115 ttl=64 time=1.463 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=116 ttl=64 time=1.907 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=117 ttl=64 time=1.103 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=118 ttl=64 time=1.573 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=119 ttl=64 time=3.620 ms

64 bytes from 192.168.64.100: icmp_seq=120 ttl=64 time=1.429 ms

Conclusion

Even though our primary load balancer went down, we saw that the VRRP Virtual IP address ensured that there was no outage from the user’s perspective in the browser. In the terminal, we saw that there was a one second ping drop, and that was about it. VRRP is an effective and relatively simple protocol to ensure high availability of an IP address by means of a failover.

This is handy for instances where only one primary loadbalancer can handle the traffic load. But if you need to load balance between multiple nodes (i.e. both lb1 and lb2 taking equal traffic simultaneously), VRRP by itself may not be the ideal solution. In a future blog post, we will explore other ways to effectively load balance the load balancers.